“Your Ability To Tear Up The Rulebook Is Your Superpower”

Adobe XD is a proud supporter of LBB. Over the upcoming months, as part of the sponsorship of the Digital Craft content channel, we will be spending time with some of the most innovative and creative minds in the industry.

In this conversation we talk with Perry Nightingale, head of creative AI at WPP. Perry’s unique role puts him at the forefront of technology’s intersection with creativity, and provides the perfect vantage point from which to chart our industry’s future. Here, Perry reflects on the ways in which AI is redefining the creative process, why living a creative life has become ‘too difficult’, and the value of believing in unicorns.

Q> We’re going to be talking a lot about creativity, so first things first - what is creativity?

Perry> Ha, that’s a big question to start off with! To be honest, it’s subjective. However, it does feel to me that it falls into two categories; information and expression.

Information-based creativity is about arranging the world in some smarter, more valuable way. An example would be moving car windows up and down with electricity rather than a physical handle. Expression-based creativity, on the other hand, is more about sharing who we are and telling stories about our experience or view of the world. Information-based creativity is what we call ‘design’, and expression-based creativity is what we call ‘art’.

If you look up ‘creativity’ on Wikipedia, you’ll be told that it is “the use of imagination and original ideas to create something of value”. But I think that both under-estimates and over-estimates what creativity is. Great art is creative because it connects us to the world and to one another, whilst rocks can be creative by sitting there and being great rocks. I tell people that if you can get up in the morning, you are creative.

I am very lucky, though, to have two unique vantage points from which look at this question. Firstly I work in technology, specifically with companies like Adobe or NVidia who provide the technologies and languages that make what we call ‘artificial intelligence’ possible. In that role, I need to understand how computers can aid or automate human creativity, to predict when, or if, they will replace billions of dollars of creative production done by hand, and I have a lot of resources at my disposal to do that research. Because of that work, I’m asked to give a lecture every year at Oxford University on whether our machines will ever be truly creative.

Secondly, and more importantly, I work in our creative industries, telling stories and hopefully enriching culture through expression. There is such a thing as a brilliant piece of creativity, that work in the jury room you wish you’d made, and there are those brilliant creative people you always want to go back to. The people from whom the ideas just keep coming and a 5 minute coffee break can lead to an act of genius.

Our machines are more amazing today than they have ever been, but I see the negative space when it comes to creativity. Every day I get to see AI's brilliance in some new way but I am blessed to get to see our human brilliance in that even more. When I tell people they are creative if they get up in the morning, it’s because I want them to realise how special these skills are, that the world’s biggest companies spend billions of dollars trying to recreate something you could do right now with a scrap of paper and a pencil for 20p.

Q> And is creativity an innately human ability?

Perry> There is definitely a strand of creativity that is about value, about usefulness or innovation. Often when I talk to consultants or business leaders they would lean towards that definition – that creativity is about problem-solving and, to be frank, making money. A lot of award-winning work these days is what we’d call ‘clever’. Animals are very capable of being clever, making tools, and machines are approaching that quite rapidly as well.

There is another strand of creativity, though, that is more about ‘art’. Typically, this will be a process of observation about the world or some lived experience in the artist’s life – the vast amount of advertising you see will fall into this bucket for example, adverts are all little social observations. There are some examples of machines doing that, the algorithm that quietly curates TikTok is probably one, but we are a long way from machines that can come up with Game Of Thrones or the next hit single. A machine will struggle to base a song on a life they never lived. It is culture, experience and society that are the innate human abilities, at this point.

Q> Can you tell me about how your interest in AI first came about?

Perry> There were a couple of key events. One was trying to build a chatbot for the Science Museum in London that made me realise the limitations of conversational AI – it made me determined to start from what machines were really capable of and building from there.

I also spent a number of years very focussed on computer vision. I did some eye-opening work for the leadership of Nike in that space, and it taught me some valuable lessons in how humans perceive the world vs an AI. We are not sat on some couch in our head watching the world go by on a cinema screen, instead we are constantly creating a little virtual movie set around us based on what we think makes the most sense given little snippets of information coming through our eyes – optical illusions like the white and gold dress work because in that little movie set you have a set of rules about what colour things are under different lighting conditions, and you’re “seeing” that and not the physical object itself.

Machines don’t have those same rules, and they don’t know anything about the world they’re looking at. That rulebook in your head you take for granted has huge implications when we start asking AI to do real world things like drive a car. For example, if you see an empty bin bag flapping in the middle of the road you drive straight through it without thinking, but that’s a decision based on what you know about bin bags not on the big black blob you are seeing. Billions and billions of dollars are being spent on that challenge and again, you do it in an instant without giving it a second thought.

Q> And what about your passion for creativity? How did that first develop?

Perry> I never used to consider myself a creative person. I taught myself to code in my lunch breaks and evenings when I was 27. At that point I was a medical secretary in a hospital in Leeds, typing up letters. Someone saw my work on my laptop, suggested I try and get a job doing it and I ended up in an agency. I was sitting in a rather austere-looking technical department and on the other side of the building was the creative department which to me looked like something out of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. That was the first time I sort of saw creativity as a tangible thing.

I kept making stuff and saying yes to things, and a few years later Creativity magazine put me in the Creativity 50 next to Ai Wei Wei and Lady Gaga, and I started to think that maybe I was creative too. Now I teach how valuable and special creativity is to us, and I work with Oxford University to find ways of measuring and rewarding creativity in schools so more young people get to have a career like this.

It's worth noting, by the way, that if it wasn’t for Adobe that career jump would never have been possible for me. I had no qualifications or anything. I joke that the only people in the world who believed in me at that point were my parents and Adobe. Today I look after the creativity of the 45,000 artists who work with Adobe products in WPP, it’s the largest creative software account in the world and we are their biggest single customer. I think it's important to have someone in that role who understands the basic power of these tools to enrich people's lives and careers, and I absolutely understand that. They saved me, really.

Q> Can you give us an example of the kind of creative work that AI is currently able to put out?

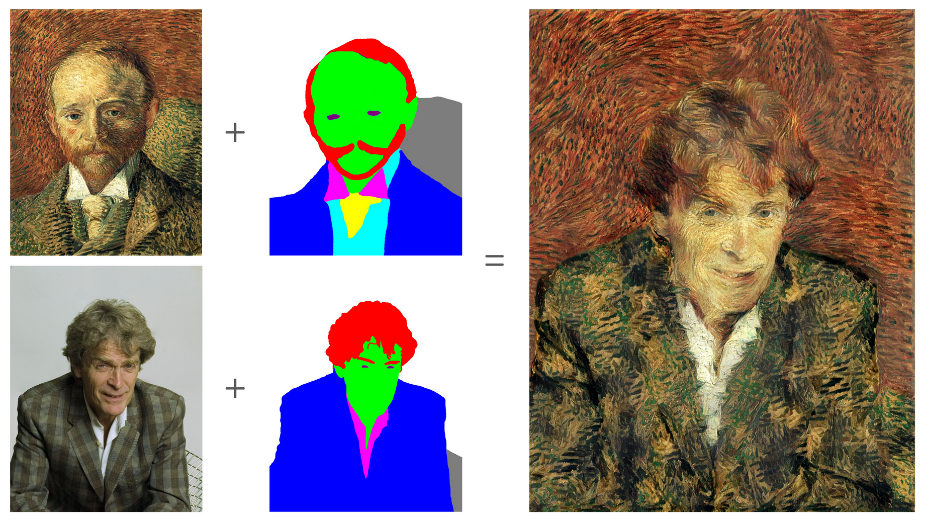

Perry> My focus is on creativity that can be enhanced by AI, using the technology to speed up our work. A good example of that is semantic mapping that helps guide an AI through the minefield that we would call ‘common sense’.

By explaining to an AI that ears and eyes are not the same, we avoid images that might be confusing to people! It comes down to those two halves of creativity, the information and the expression. Most of the image is just pixels and brush-strokes, I move them from one image to the other, but a small portion of it is the eyes and the look he’s giving and those bits have to be done by hand.

Above: An image of BBH Founder and LBB Chairman Sir John Hegarty, recreated in the style of Van Gogh by an AI software. “The photo shows the process of adding semantic maps to the photos and giving that to the AI”, explains Perry.

Q> If I were a creative employed by an agency, should I be scared of AI?

Perry> I think the short answer is yes, particularly in some instances and depending on the type of creative. Creative production is one area I look at very closely, because AI is going to be increasingly important for us in generating artificial film sets, voices or actors. These are human roles that are vulnerable to automation in the future.

As the wider industry is becoming increasingly mechanised and automated in its content delivery, a lot of the growth of the industry is going into short-form targeted programmatic media where data and AI play a creative role by rearranging clips or assets on-the-fly. In these formats, it is harder to make expressive work. Each year we make less and less 60 second films.

It’s important to remember that AI is not robots and talking cars, it’s not suddenly going to come up with a big campaign idea, instead it will sit behind the scenes quietly making things faster or more effective but that can have a big impact on the sort of work creatives are asked to make. I spend a lot of time explaining to clients that human creativity is critical for empathetic long-term brand building, but that doesn’t change the fact that nowadays people consume targeted media in less time in more places.

Q> Does anything about AI scare you?

Perry> I’ve seen so much stupidity from AI that it's almost impossible for me to be scared of it! The human avatar videos that Synthesia produce have a creepy quality to them at times… I think if one of them appeared in a work setting, telling me to improve my performance or something, that would be unnerving. We are rapidly handing power to algorithms in areas like recruitment and justice, so a virtual boss is not inconceivable.

Perhaps another scary thing is that these AI-driven algorithms are also good at being addictive, constantly giving us one more thing to click on or scroll through.

Q> You’ve said in the past that you believe in unicorns. When you’re working with AI, does it help to have a fantastical or utopian disposition

Perry> Haha, I’m not a flat-earther or anything. Reality has always been fluid to me, I have seen a lot in my life and often lacked the structure most people have, and I feel that even more keenly now as an artist to be honest. I know what it's like for society to be taken away. I would say that what’s happening this year is a fantastical experience for most people - one day everything was normal, then we woke up and suddenly people were walking around in chemical-warfare suits carrying industrial quantities of loo roll.

I don’t know if working with AI specifically has made me more or less inclined to believe in fairies and unicorns, but gravity and creativity are far more mysterious than a few tiny people with wings or horses with horns and yet no-one seems to care about those. You are stuck to the floor right now and we have no idea why. That thought you just had in your head? We have no idea how that happened either. This is a deep and mystical world with plenty of room for belief and faith. If there are no unicorns in the fossil record in this universe, then maybe they’re all in the universe next door. Or hiding in the sun, as my five year old daughter confidently informs me.

Q> With the kind of AI tools that are beginning to appear in the market, high-quality creative work will become easier to make for millions of people. Do you worry about cheapening creativity?

Perry> That’s definitely something that I am conscious of, that in removing the basic craft we accidentally take away something important to how we develop as artists. I know someone who went to one of the leading architecture schools in Europe and all they did for the first two weeks was learn to draw dots. We’ve all done repetitive menial work in our early careers, but I’m open to the possibility that we gain an understanding of something in doing that which becomes valuable later on.

Then there’s also the sheer economics of it, that having machines doing the work of junior creatives means those young people will need to look elsewhere for jobs and I don’t see them returning to the industry to do the higher-value craft later in their careers. On the other hand, these tools and software programs make it generally easier for people to learn and access our industry with subscriptions and personal licences getting people that all-important first step. That’s how it was for me, so it sort of balances out.

Q> Regardless of AI’s impact, do you feel that creative work, or ‘content’, has already become too cheap and disposable? And is there any way in which AI could remedy this?

Perry> Yes and no. I think it’s harder to make a living as a musician now because of the proliferation of content, for example. My friend contacted me the other night to try and track down an old album, from Paul Oakenfold’s two year residency at Cream, so around 1997. Back in the day we’d listen to that album on repeat because there was simply less music immediately available before the days of Spotify and SoundCloud. The same thing happened with printing of visual art before that.

Social media goes some way to fixing that, in that you can create quite a tailored audience for your work. But at the end of the day it's more difficult to live a creative life than it should be. Something is broken in how we value expression-based creativity in society, and I am trying to fix that.

Q> Finally, your role puts you at the forefront of what’s new, forging the future. But you must take inspiration from somewhere? What stuff inspires you day-to-day?

Perry> I have two small children and they are amazingly inspiring. They probably started to outdo our machines at creativity and natural language processing from the age of two, and it’s fascinating to watch them say and do things that I know these giant companies will never achieve. They constantly fill the gaps in their world with amazing little ideas and stories. Great business leaders like Elon Musk and Steve Jobs have child-like approaches to the world, they fill the gaps in reality with new and better things. That rulebook you’ve built up in your head over your lifetime is powerful, but your ability to rip the whole rulebook up when you feel like it is probably the greatest superpower of all. That’s what believing in Unicorns is really about.