Why Ryff Does Not Recommend In-Game Advertising

Look out! You’re about to crash your car head-on into the billboard!

If you are going to tackle an old problem, you need to have a new way to do it. In the case of video game brand and product placement, it has been attempted previously but failed each time.

In-Game Placement fails to deliver for brands and loses money for investors for the very same reasons. This does not mean that a new way of doing something cannot solve the problem, as has been proved with VPP by Ryff. But it does mean that if you tackle an old problem, you need a new solution. The latest entrants, such as Bid Stack (LON: BIDS), Anzu (anzu.io), and Admix, are bringing an updated approach to the problem, but the fundamental and deployable solution remains functionally the same as previously tried.

Back in 2006, Microsoft spent $400M on purchasing Massive. Microsoft planned to implement Massive's dynamic in-game ad solutions into several services, beginning with Xbox Live and Xbox 360 titles but stretching to other online activities such as its casual games space through MSN and Windows Live, followed by Sony's purchase of Double Fusion. Both were ripe with promise and ambition but failed to deliver a scalable solution. Massive was shuttered four years later. It wasn't necessarily the fault of the vision but rather one of timing. The advertising market was not ready to adopt.

Tools and standardisation to bring in-game advertisements at scale still do not exist anymore now than back during the Massive days. At the time, they were on the supply side, the side of the game developers. There needed to be more standardisation in game engines; right now, even though we have Unity and Unreal, neither offer helpful APIs to third parties for in-game advertising because neither wants to give such value away despite them wanting to do it themselves for alienating players.

The Microsoft deal may also have contributed to Massive's supply-side issues. Following the acquisition, Massive worked almost exclusively with Xbox titles, while PlayStation had an exclusive agreement with competing in-game ad firm Double Fusion. They divided a market that wasn't big enough then and is still not today.

When we look at the adoption of programmatic advertising across other entertainment platforms, an advertiser does not know ahead of time which publisher, platform, or even specific media their brand will appear. They want to hit their clients' GRP (Gross Rating Point) targets. While games give audience sizes, they fail at engagement, brand/product recall, do not deliver positive sentiment, and do not bring about intent to purchase.

Anzu came up with research that showed gamers find in-game adverts make the game 'realistic.' We've been told that heavy gamers don't mind advertising in their video games. But a study from ComScore Media Metrix confirms many other findings. They found that "heavy gamers" (those who game at least 16 hours each week) seem receptive to in-game advertising.

The data also indicates that 37% of these gamers agreed that adding ads made games more realistic. While this is higher than the 27% of light and medium gamers who agreed with this statement, advertisers should take note that 73% of more casual gamers do not agree.

This simple fact is lost in many discussions about video game advertising, where statements such as "gamers like the realism advertising brings" are trotted out uncritically, usually by those with ads to sell.

The reality is that many people do not feel this way, and many reject the encroachment of advertising into every facet of life, especially into purchased products (free stuff is another matter).

It comes up in these cycles because the pitch is so easy. Games get more hours of eyeballs than TV. We can give you the eyeballs.

Gamers don't see games like consumers see TV adverts or product placement. This mock up perfectly illustrates gamers' attitudes toward it.

Geeky Gadgets - In Game Adverts

The Core Issue – Foveation

Watching TV, film, and even sport, the human visual system 'sees more' than in the fight or flight mode created by video games. We need to focus on where attacking animals' razor-sharp teeth are, which hand is holding the sword, or where a rifle shot originated from. Those scenarios need us to narrow our field of view and concentrate hard.

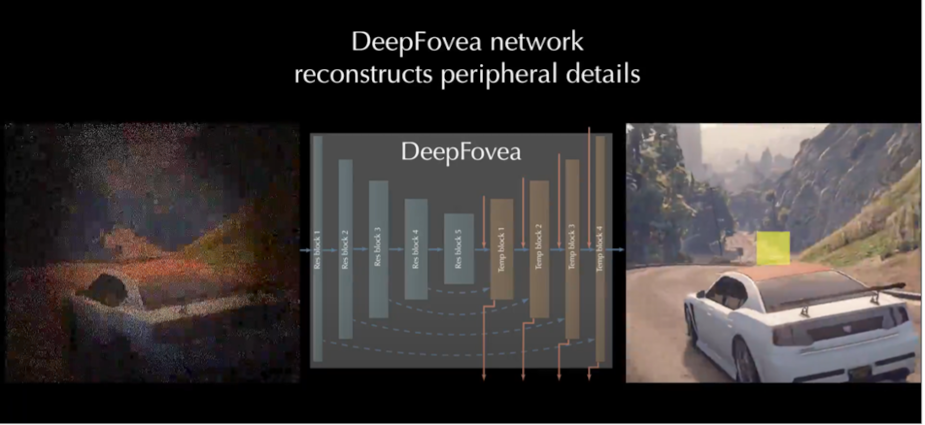

Microsoft tutorial on foveated 3D

It cannot be any other way. This narrowed view is apparent in the green box above. In entertainment mode, we are more relaxed and can see the things taking place in the red box above but with less detail.

Focusing is exhausting. This is why people playing video games or engaging in VR get hot and sweaty—moreover, being distracted while in fight or flight, mode is intensely irritating (and in the real world, life or death is dangerous). Directed Attention Fatigue (DAF) is a neuro-psychological phenomenon that results from the overuse of the brain's inhibitory attention mechanisms, which handle incoming distractions while maintaining focus on a specific task.

The greatest threat to a given focus of attention is competition from other stimuli that can cause a shift in focus. I.e., in-game advertising!

This is because one focuses on a particular thought by inhibiting all potential distractions and not strengthening that central mental activity. Directed Attention Fatigue occurs when a specific part of the brain's global inhibitory system is overworked due to the suppression of increasing stimuli.

Facebook's AI Reconstruction May Help Solve Foveated Rendering

This excellent, concise video (above) from 'Facebook's AI Reconstruction May Help Solve Foveated Rendering' illustrates this further (and very well). When we play games, our brains and visual system work differently than when we look at and watch storytelling.

Look at the adverts or placement and die/crash/miss/lose.

Business Insider Image

In gaming, those eyeballs aren't looking at the thing you want them to see. Here is an in-game advert for Intel in PUBG. I played this a lot personally (Roy Taylor). The gamer looking at this ad is dead about the exact second he looks at the advert. In fact, in a fraction of one second.

The math behind it is easy to understand:

When you react to something like an enemy coming into view, your brain has to receive a visual signal from your eyes, process what that signal means, decide to react, then send a new signal down to your muscles where your muscles contract.

Ask jackfrags what he thinks of in game advertising (jackfrags YouTube)

How fast do gamers play, and what does it take to pull off winning regularly? This video is a good illustration:

Many players are shockingly fast. The speed at which your brain receives the original signal, and sends a new signal to your muscles, is very fast. It's about 110ms (A millisecond (from milli- and second; symbol: ms) is a unit of time in the International System of Units equal to one thousandth (0.001 or 10−3 or 1/1000). But the middle part, where your brain needs to process the incoming information and make the decision of how to react, is where this process starts to slow down.

In our simple scenario where you are waiting for an enemy, you see them come into view and then execute the action of shooting them. This likely takes about 250ms for you to react fully. And over half of this process, about 140ms, is when your brain processes the information.

The Worst is Yet to Come

Gamers don't like cheesy, lame placements. They loathe them.

Unlike TV viewers, gamers are vocal and quickly create trouble when they don't like something. There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of examples of players rallying on social media to slam down a game with in-game advertising.

This one works as an example of many. It's a boxing game from September 2021.

Attached is a link to a clip from NBA 2K, which features a virtual Jake from State Farm in a cut scene.

There were some conflicting views on his intrusive appearance as a character in the game. But he was featured again in the following year's version of the game

But what about Esports and Twitch?

There are some good arguments for saying that game adverts work for esports because the viewers are not playing. The Twitch esports numbers for 2019 are good; 443 million. But the advertisers generating good results are in and around the gamers but only in the games themselves as a 2D overlay, much like we get with 'ticker tape advertising.' In this video, I know first hand that Asus got some excellent results - for the chairs.