Is This a Malfunction? Behind The Glue Society’s Brexit-Inspired Installation

This week, creative collective The Glue Society has debuted its latest installation at the London Design Festival 2019: the Brexit- inspired piece “What Were We Thinking?” The large-scale installation inverts the familiar mechanics of a forklift, depicting a conspicuously airborne machine overwhelmed in its attempt to raise a wooden crate. The piece will be featured as part of the Festival’s London Design Fair, and accessible to the general public, located at the Old Truman Brewery complex from September 16th-23rd.

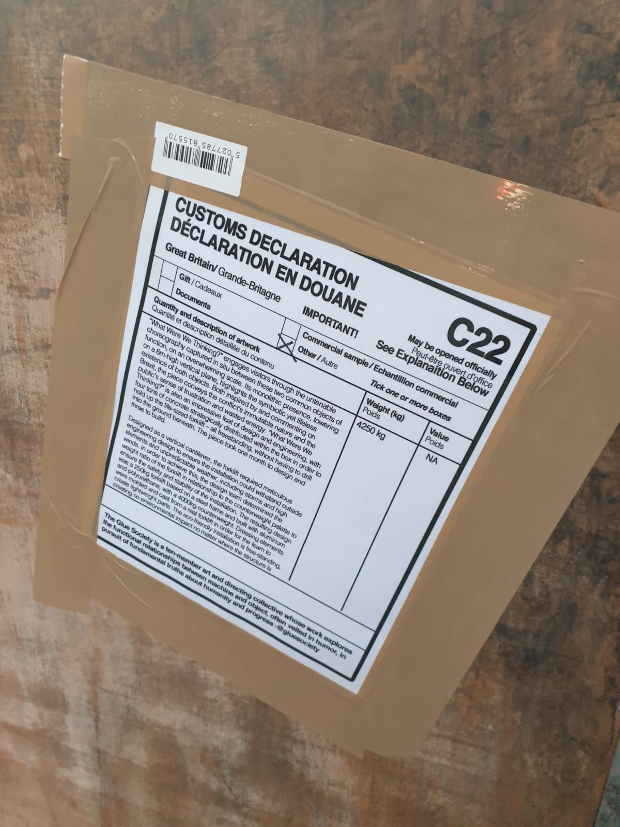

To ensure it worked as a free standing structure, the weight ratio of the forklift in relationship to the counterweight palette needed to be perfect. The resulting design was a 25 kg forklift with a 4000kg counterweight.

It’s hard to miss when you walk past, although when LBB’s Alex Reeves met Glue Society member Henry Curchod for a chat next to the installation, it’s surprising how many people walked past as if it was a totally normal scene.

LBB> As a collective you’re based in Australia - what was the outsider’s view of Brexit you wanted to bring to London?

Henry> There are about ten of us permanently at Glue. And six or seven are English. I’ve lived in London and Brighton, so I’ve been part of this thing before. It gets talked about everywhere in the world. It’s like a Trump thing.

Jonathan Kneebone, the founder of The Glue Society, is from London. He’s particularly close to the idea. We talk about it, but it doesn’t immediately affect us. We all have a connection to this place but we’re all overseas and in and out of the country all the time.

The whole world is thinking we don’t know how we’ll be able to interact with the UK after this. We have major relationships with the UK, but not as citizens. We don’t know what’s going to happen. So we’ve been thinking for a while what we might say about this.

What we all really liked about it is for us it’s more about talking about the feeling of the times, the Zeitgeist, rather than trying to make a point either way or argue a perspective. Because there are arguments either way and if you align yourself with one person… We were wondering how we could illustrate the sheer sense of frustration and weightlessness, lack of functionality of something without having to make a point about it. And we thought this is probably the funniest way. We like humour.

LBB> Most of your work has fun with serious issues. Is making people laugh important to you?

Henry> Yeah. It’s hard to access people if you’re not making light of something. For people to relate to something you have to make it funny, I think.

LBB> What was the start of the idea?

Henry> Our collective has a warehouse and the warehouse across the street has this particularly beautifully aged forklift outside - you see it dropping palettes sometimes. One day someone said, ‘why don’t we make a forklift that goes the other way?’ People started talking, one idea led to another until we decided to reverse the function and get it as high as we possibly can, which we thought was going to be about seven or eight metres… but science exists.

All of our ideas come like that. We hang out. We see something, comment on it and then all of a sudden there are sketches and ideas and it’s happening.

When you present an idea like this to a structural engineer and a production designer (because obviously I’m not going to do this myself - I’ve got no clue how to do this), it turns out another metre would have required eight tonnes in the box [the final box weighs four metric tonnes]. If you go higher it starts to tip. The height is what matters. That’s the way vertical cantilevering works. I had a really in depth explanation, but I don’t fully understand the physics of it. Also, we didn’t want to make the box too big. That’s a standard sized crate. Any bigger and we can’t go any higher.

LBB> How did you actually build it?

Henry> We had to go and find the forklift, we bought it, then we moulded every bit of it. Everything that was metal was remoulded out of ultra-light aluminium. Then we remoulded the rest out of poly. We made an entire forklift with the most lightweight versions of the materials it’s made from, which is annoying and time consuming and costly. It took a lot longer to do than initially anticipated.

There are elements of it that work but it can’t go all the way up and down. The motor’s been taken out because it was very heavy, but you can put the motor back in. It’s an exact reversal of the forklift mechanism. We kept the integrity of all the mechanics. It’s just flipped.

It took a long time. We built out west of London, brought it here on a flatbed truck, put the box down, attached the forklift and then we laid each brick of concrete one by one in the box. There are 200 bricks of concrete.

We had to do it for real. The forklift drivers are baffled. They’re driving past, staring at it going, ‘That’s not how they work’.

Normal forklifts weigh two and a half tonnes, generally, so it is almost a complete reversal of the weights of the two objects. We made the box the weight of the forklift and the forklift the weight of the box.

For me personally the most beautiful thing is this yin-yang of weight. The vertical cantilever of these two things that look like they should be constantly spinning, toppling, are suspended. It’s a quietness that I think we need.

LBB> How have people generally reacted so far?

Henry> I’ve only been here for the last half an hour and the most common comment that we’ve had is, ‘is this a malfunction?’ ‘Is something wrong?’ And when you say it’s art they go, ‘Oh!’ And then they start exploring it. It’s not until a functional object has lost its function that we start to reassess. And they ask us what it means, see the Great Britain [flag] sticker and they say, ‘Is it a Brexit thing?’ So it’s a train of thought that people follow similarly.

I think it’s important to let the thing sit as its own formal structure. It’s not a piece of activism. We’re not saying anything about Brexit. We’re just explaining the frustration that’s an undercurrent in not only British society but in all our societies. America’s worse. There’s a lot of uncertainty and questioning of processes. Are we making progress? Are we really doing anything to help ourselves?

If you take something, put it in a different place and reverse its structure, people want to believe that it’s not a piece of art.

LBB> Apart from the physical challenge, what were the big considerations behind the project?

Henry> It was really about convincing ourselves that it was the right idea to convey something - that it had the right amount of ambiguity. We don’t want to be in your face. So it was leaving people to make the connections on their own. We don’t want to walk past and feel that they’re being fed an idea. We want people to walk under it and feel weightlessness and a sense of heaviness.

LBB> Social media has definitely turned a lot of art into a selfie opportunity. How do you feel about that?

Henry> I love Olaffur Elisson but I went to his exhibition [at the Tate Modern] yesterday and I couldn’t move. So many people go to the Tate, there are so many people and it’s a cultural place, but when things are hidden you get to be alone with them. It’s making public art outdoors even more special because you come across it and find it by accident. As opposed to queuing up to see a ticketed thing. Public, free art is going to become more important in the future.

The installation is going to change every day. The construction site is going to evolve. It’s going to be quite hectic here. At the moment it’s nice because there’s lots of space. So people walk around it and get to notice it and then feel like they’re alone with it. Feeling like you’re alone with a thing like this is special.

Photo credit, top: Tom Gildon