Brazil’s Horror Genre Is Having a Revival

Jardim Ângela in As Boas Maneiras (Good Manners, 2017)

What better time of year to talk about Brazilian horror films than the week before Halloween? It’s not my usual territory. I’m more of a Mary Poppins fan. But after stumbling into a room in Clubhouse earlier this year (remember that phase?) discussing low budget production and horror films, I thought it was time to get familiar with the genre.

Brazil, it turns out, has something of a cult status amongst horror fans, having had a golden age – or perhaps dark age would be a better phrase – from 1963 to 1983. I’ll dive into the history later on, but what I hadn’t appreciated was the revival that Brazil’s horror genre has had in the past decade. In 2008, there were just three horror films released in Brazil. By 2019, that number had jumped to 37.

By way of background, I’ve run a production company in Brazil for the past 16 years helping foreign productions film over here. Our HQ is in São Paulo – South America’s largest metropolis and the setting for some of the best horror films released in the past few years. A few months back, I decided to immerse myself in the genre, past and present. The process turned out to be akin to a Clockwork Orange aversion therapy experiment, forcing myself to watch violent, terrorizing films, often through the night while my family was fast asleep. It was worth it, though, as it’s a great way of understanding Brazil in its filmmaking context and its turbulent history. What stood out were the heroic efforts of trailblazing independent filmmakers and creators on a quest to tell a story and find their audience.

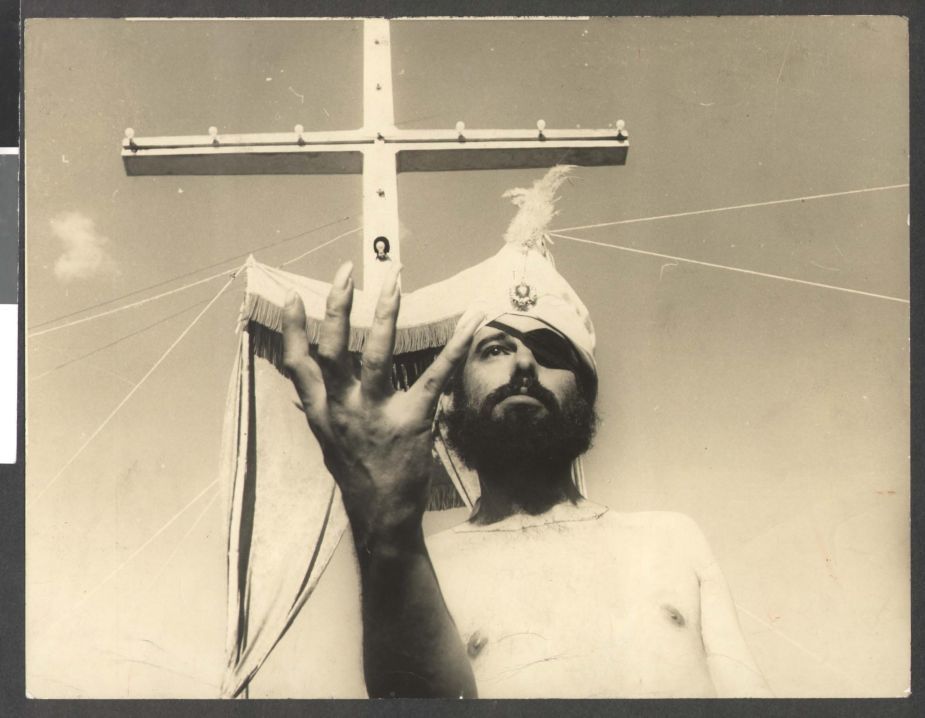

The undisputed king of those trailblazers was José Mojica Marins, the father of Brazilian horror whose films span the late 1950s to the 1980s. He was making ultra violent films while Hollywood still had censorship. I spoke to the Brazilian director and screenwriter Dennison Ramalho who is something of a spiritual heir to Mojica, and had the chance to work with his idol in 2006 on the making of Encarnação do Demônio (Embodiment of Evil).

José Mojica Marins

“If Brazil has somewhat of a reputation in the horror genre it’s because of Mojica and his character called Zé do Caixão, known as Coffin Joe outside Brazil,” says Ramalho. “Coffin Joe is a character created by Mojica who was both the director and the actor playing the character. It’s a unique case in the history of horror films around the world because he’s the creature and the creator who were mixed in an almost inseparable way. His films were discovered outside of Brazil in the 1990s and became instant cults.”

Dressed in black from head to toe with a top hat, the sadist Coffin Joe had long nails and ‘tested’ unsuspecting women in search of the one who would conceive him a son as the perfect human being. In his wanderings through the countryside, Coffin Joe tortured people and mocked common Brazilian superstitions. Mojica was a self-taught filmmaker and made most of his films in São Paulo’s Boca do Lixo era.

“The Boca do Lixo was a prolific cycle in Brazil’s cinematographic production between the late ‘60s and the early ‘90s,” Ramalho explains. “It was called Boca do Lixo [literal translation ‘foul mouth’] because there was an area in the centre of São Paulo that was home to lots of production houses and distributors, and all of Brazil’s ‘porn slapstick’ and erotic comedies were produced there. X-rated Brazilian cinema started there too. There were some horror films made in the ‘70s and ‘80s in the Boca do Lixo, but they were almost all for a male audience, sexploitation horror films.”

Despite Mojica’s commercial success during this era, the horror genre didn’t manage to take hold in Brazil, Ramalho told me. Horror films simply weren’t being made on a regular basis. Despite finding his audience during the dictatorship in Brazil, Mojica’s films weren’t political. “The new cinema era in Brazil was very political with allegories and even accusations of the problems of the military regime. But Mojica was making horror films without any type of political anchorage. He was an exploitation filmmaker, he wanted to impress, to shock and always described himself as a sensationalist,” says Ramalho.

Ramalho was a horror genre cinephile before he began making his own movies. He directed three shorts – all hits on the international horror film festival circuit – before working as co-writer and assistant director with Mojica on Embodiment of Evil, released in 2008. Since then, the genre has flourished in Brazil, and Ramalho is one of its stars. His 2018 film A Morte Não Fala (The Nightshifter) was based on stories written by Marco de Castro, a former journalist who reported on violent crimes that took place in the perifería of São Paulo – the low-income outskirts of the city.. “Marco de Castro’s material is based on his own experience as a reporter; people he knew, favelas he visited, slaughters he witnessed,” says Ramalho. “It’s a really rich universe because it’s extreme and raw, telling stories lived in a harsh reality in São Paulo, in the periferia.”

A Sombra do Pai (The Father's Shadow, 2018)

Other contemporary directors have set their horror films in the perifería of São Paulo. In As Boas Maneiras (Good Manners, 2017) by Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas the story of a werewolf is developed in the middle of the São Paulo metropolis, giving a fantastic fable-like air to the urban landscape of the largest city in Brazil, contrasting the isolated pocket of luxury in Alphaville and a large shopping centre with extremely poor areas such as Jardim Ângela. Something similar happens in A Sombra do Pai (The Father's Shadow, 2018), by Gabriela Almeida, shot almost entirely in a house in the São Paulo neighborhood of Butantã – a parallel of the coexistence of the city’s crowded housing estates and decaying old houses. In the film, a father and his young daughter try to revive her dead mother with rituals performed in the decrepit backyard of the house where they live.

Alphaville in As Boas Maneiras (Good Manners, 2017)

“The horror genre in Brazil over the last ten years is colourful and really diverse,” says Ramalho. “From the folkloric films like Rodrigo Aragão’s Mangue Negro (Mud Zombies, 2008) and O Cemitério das Almas Perdidas (The Cemetery Of Lost Souls, 2020) to films that have strong commentary about the bourgeoisie such as Gabriela Amaral’s O Animal Cordial (The Friendly Beast, 2018). The films go beyond dealing with social questions, and the setting of the Brazilian clichê of periferías and favelas and such like. I’d highly recommend people watch this films”

Last but not least, I would like to add my own special Halloween viewing recommendation – Pinball a short directed by Ruy Veridiano and shot by DOP Alziro Barbosa. It’s the story of a young man who attempts a voodoo spell that goes wrong, runs from the cemetery and finds himself face to face with Death in a badly-lit run-down arcade. He attempts to trick Death in a final game of pinball.

Are you brave enough to watch them?

Nick Story is executive producer at Story Productions Brazil