Behind The Work: Chadwick Boseman's Unforgettable Last Film, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a transportative piece of art. The biographical musical drama, directed by George C. Wolfe, is a celebration of three legendary blues musicians, with a focus on Ma Rainey herself – often referred to as the “Mother of the Blues.” Ma Rainey is portrayed by Viola Davis, a performance that earned her an Oscar nomination at the 2020 Academy Awards. The film took two Oscars home in the Best Costume Design and the Best Make Up and Hairstyling categories for the way it transformed the cast into the blues stars of the period. There’s a bittersweet note to the film too, as it was Chadwick Boseman’s last on-screen performance, lauded as one of his best by fellow actors and critics alike.

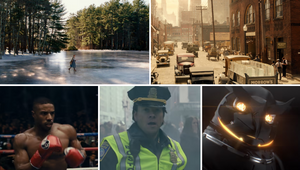

Part of the film’s magic is the way it conjures the atmosphere and texture of 1920s Chicago and its bustling music scene. ZERO VFX were tasked with recreating a specific tone, mood, and environment of the time and place; the melting heat and rush, and the electric excitement of the music itself.

Making it happen wasn’t easy but ZERO were up to the task, combining in-depth historical research and artful craft. With Pittsburg standing in for a Chicago of a bygone time, Brian tells LBB how they used VFX technology to transform it into Wolfe’s vision of The Roaring Twenties.

LBB> We loved the film and it was wonderful to see it rewarded with two Oscars. How did you get involved in this project – had you worked with George C. Wolfe before?

Brian> Thanks! We would have also loved to see the amazing leads recognised by the Academy, but that’s well out of our control. But really, all the departments on this film really hit a home run.

Though this is our first project with George, we’ve had a long history working with both Escape Artists, the production company, and Denzel Washington, who served as a producer, and has committed to bringing all of August Wilson's plays to the screen.

LBB> What was your initial approach to the brief from the director?

Brian> Overall, as an adaptation of a play, we knew this story would have very few exterior scenes, and moreover, most scenes occurred in only a few rooms. Thus, when our camera takes us outside, into the heat of the Chicago summer (which we shot in Pittsburgh), we really needed to connect the audience to these moments. We worked with George and Mark Ricker, the production designers, to carefully research what it really was like in the mid 1920s and faithfully reproduce it both practically with set dressings and with our digital environments.

LBB> You've worked on a lot of great projects, but what was it like to work on Ma’ Rainey’s Black Bottom and to be a part of telling the story of the “Mother of the Blues”?

Brian> It was really pretty awesome – Don Libby, ZERO’s VFX supervisor, and I soaked up the history surrounding this story, and speaking for myself, learned a ton about the history of our country, the great migration, the hopefulness the new residents brought with them and the industrial complex that in a way preyed upon this hopefulness. All these feelings needed to come through in our work.

LBB> At what stage did you get involved with the project and how did it impact the work that you did?

Brian> We were in early, as we are with most of our films – reading early scripts, envisioning how and where VFX can help the film-makers achieve their vision.

LBB> Much of the aim of the VFX in Ma Rainey's Black Bottom is to be unnoticeable to the untrained eye. How much VFX was actually involved? How long did the project take end to end?

Brian> Our involvement was for at least nine months – from pre-production through to final delivery. The main focus of our work was to create a digital, 1927 Chicago from a few vantage points – hot, treeless, and filled with bustling activity. Mark Ricker and Tobias Schliessler, the DP gave us some great foreground action to work off, generally within the first ½ block of the camera, and we took it from there. We created a CG elevator train, CG vehicles, digi-doubles, fully CG buildings, telephone poles and a really heavy, dense atmosphere. As an east-coaster, whenever I see these shots, it reminds me of the hottest, most humid, smokey, and sticky summer days I remember.

LBB> How closely did you work with the director George C. Wolfe on this project?

Brian> We worked with George, almost daily at times. As the film was edited, it became apparent that an opening montage needed some heavy concepting, design and execution. These are slice-of-life, showing some of the industrial settings, people working in these places and a big push-in to a theatre façade. This montage really was high-concept and Don Libby got the chance to really dig in with George and translate what he wanted the audience to feel into tangible imagery.

LBB> You oversaw all the set work for this film. Was this a big job considering this was a period film?

Brian> We had some really big setups, so some big days, but then for probably like 80% of the film, the rest contained smaller VFX needs and clean-ups.

LBB> Which of the scenes / shots were the most labour intensive from a VFX perspective? Tell us why.

Brian> Our hero set extensions were the most labor intensive. Only ½ of a block of our practical location had period-correct buildings and set dressing. We needed to extend that over four blocks as well as add the skyline of 1920s Chicago. We LiDAR-scanned the entire location to aid in tracking and layout for the extra city blocks that we needed to create. Using the Oscar-worthy production design of the set for inspiration, we designed the CG buildings, set dressing and matte paintings needed to extend the set to the horizon. Once in editing we realised the city streets didn't feel busy enough. The director wanted more background action than we captured on the shoot day. We ended up adding multiple CG vehicles and pedestrians, and had to seamlessly integrate into what was captured on camera.

LBB> Did Covid have an effect on your usual working practices and, if so, how did you navigate that?

Brian> We wrapped our work on this film in April of 2020, so it was getting delivered while our office was going distributed – it was a fun month!

LBB> Did you encounter any other challenges while working on the project? How did you overcome them?

Brian> After principal production shots were conceived to fill out the opening montage of the film. They were vignettes of factory workers and people en route to Chicago from the south. First, we concepted the shots with the director, then shot talent and set dressing against a green screen. Fortunately, part of our integration process is to spend any downtime looking for interesting stuff to capture for reference. While in Pittsburgh, we extensively photographed and scanned anything nearby that would have been functioning in the 1920s. One location was a massive blast furnace that was the size of a small town. Using assets from that one location we were able to create multiple photoreal 2.5D environments, which served as backdrops for our montage vignettes.

LBB> What was your favourite part of working on the movie? What have you taken away from the process of working on this film?

Brian> Overall, it was a very interesting project from start to finish. Despite the very big names attached, the production had a very indie feel. It was very much a passion project for all involved. There were plenty of moments where ideas would come up and we needed to find creative ways to execute on the spot. Also, nothing was done just for spectacle or production value. Everything we created was to serve the purpose of the story, which is exactly our passion.